終于播出了香港電臺RTHK31的訪問,MagicWilson溫思聰分享他從會計師,成立顧問公司透過魔術作企業培訓,後來因身體問題後創立了香港愛心魔法團的心路歷程,及如何和兒女承傳愛與關懷的精神。他如何透過魔術和愛心魔法轉化心靈,化成激勵人心的動力,請在RTHK YouTube頻道收看,同時記得給個Like!

人才發展頻道預告資訊:本學苑苑長溫思聰MagicWilson接受香港電臺RTHK31訪問《凝聚香港》雙軌人生-第970集

人才發展頻道預告資訊:本學苑苑長溫思聰MagicWilson接受香港電臺RTHK31訪問《凝聚香港》雙軌人生-第970集(2026年3月6日晚上630pm時段RTHK31播出)。本學苑苑長溫思聰MagicWilson接受香港電臺RTHK31訪問,分享他從會計師,成立顧問公司透過魔術作企業培訓,後來也創立香港愛心魔法團的心路歷程。他如何透過魔術和愛心魔法轉化心靈,化成激勵人心的動力,我們到時收看!

事業、人生、魔法 – 從會計師到人生魔術師 (普通話講座)Change Management by MAGIC – MagicWilson Wan 溫思聰

愛心魔法學苑 – 人才發展頻道(2026年2月7號發佈)

身兼 會計師 · 社會企業家 · 企業策略顧問的 Wilson WAN 溫思聰 (人稱 Magic Wilson) 於2026年2月2號爲一衆定居在香港面對職場上轉型的學員首次全程用普通話分享他的生涯故事,從2003年SARS面對財政低谷,創立MAGIC成功學到達2005年當時事業的高峰,再由於家人及自身健康問題再次掉進生活的低谷,面對死亡邊緣後2009年創立慈善團體香港愛心魔法團,經歷不同階段的轉型突破,復出後2024年底再創立愛心魔法學苑這個共融社會企業平臺,從本心再出發的心路歷程。當天他也跟大家分享了成就商數Miracle Quotient(MQ)、夢想領航零點理論,和陳志輝教授所創的左右圈研究應用,跟大家共勉之!「人生就如魔術 ~ 變化快於計劃…」https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGDtizk8E1s

2026年1月24日義工嘉許茶聚

爲感謝一衆「香港愛心魔法團義工協調小組」的愛心魔法義工一直以來的支持和無私奉獻,「香港愛心魔法團」在「香港愛心魔法團義工協調小組」主席Margaret的統籌下於2026年1月24日舉辦了2025年的義工嘉許茶聚以感謝各位2025年間熱心服務的義工(尤其是代表本團參與服務了「第十五屆全國運動會香港賽區義工計劃」的30多位愛心魔法義工(特別是:小組組長謝桂珍、阮愛玲、關艷芬)。茶聚當天感謝各義工出錢又出力,準備了各款美味和別出心裁的美食,也感謝永明金融有限公司贊助場地,感謝本團創團理事會副主席方錦聰先生Kenny和特別嘉賓Magic Michael LAM到場支持並爲大家分享了精彩的心靈魔術,感謝張懷基分享和教授小魔術、鄧玉群的剪紙教室、本團創始人兼創團理事會主席MagicWilson溫思聰也出席支持和跟大家愉快地歡度了半天。感恩有大家,社會變得更美好!

香港愛心魔法團義工協調小組2026年首次愛心魔法義剪服務

踏入新的一年,在2026年1月5日,香港愛心魔法團義工協調小組安排了多位義工(龍惠娟、張懷基、王煒琪、陳燦忠、梁月開、林少芬、周文英、周桂英、黃詠賢、郭淑娟、羅文苑和黃凱儀),浩浩蕩蕩地走進香海蓮社普光學校為有需要的學生提供一次剪髮體驗,亦為作爲照顧者的家長打打氣。當天雖有個別參加者大地哭,但愛心魔術師立即獻上小小的愛心魔法緩和了學生們激動的情緒,義工們運用熟練的剪刀,耐心地為小朋友們打造靚靚的髮型,亦讓照顧者們(爸爸媽媽)欣然地見証子女們克服心理關口(包括恐懼理髮和與陌生人接觸),帶著靚靚心情上學去。再次我們感謝義工們的愛心、耐心、善心和無私奉獻出寶貴時間,齊心合力去面對另類的挑戰!

2025度《蝶影翩翩》攝影比賽

準備好您的眼睛和相機,2025度最令人期待的攝影盛事——《蝶影翩翩》攝影比賽綻放光彩!比賽由國際自然生態學學會和蝶影迷蹤 聯合主辦

請大家也多多支持,見證大自然美麗的一面!

Magic and Improvisation

Magic and Improvisation

WAN Sze-chung

Head of the Academy of Caring Magic Limited, Hong Kong

Published on 16 March 2025

“Changes go faster than plans”, especially in the dynamic business environment nowadays. The ability of improvisation has prime importance to team performance.

Improvisation is subject to changes, first-time and redirection while an individual can predict and explore the possible ways of development by relying on what had happened and what continued to play (Barrett 1998, p. 151). By reciting Moorman et al. (1998), Akgun et al. (2002, p.117) points out that the term “improvisation” comes from the word “improvisus” (a Latin word) that means “not seen ahead of time”. In other words, it is also interpreted as putting plans and implementation together with immediate actions while it is about designs and processes that are continuously reconstructed. According to Weick (1998, p.544), the prefix “im” gives an opposite meaning. “Improvise” also refers to the opposite meaning of “proviso” while “improvisation” is about dealing with those unforeseen and without fixed rules beforehand.

Improvisation has been adopted in different areas, ranging from performing arts (such as Jazz improvisation and theatre improvisation) to team improvisation, requiring individuals to think quickly and adapt to fast-changing environment with innovative solutions. Wan (2006) applied Magic, with the concepts of spontaneity, motor skills, problem solving skills, attention, cognitive skills, psychological skills and perception, offers an effective tool for developing such improvisational skills. Magic tricks often involve elements of misdirection, spontaneous thinking, and adaptability, making magic an effective tool for improvisational training. Misdirection, a fundamental technique in magic, teaches individuals how to guide audience’s attention in an effective way, and translate the skills to manage focus (Hugard & Braue, 1974). On top of that, one’s ability to recover and manage the situation from a failed magic trick or performance requires high level of resilience and adaptability, which are essential qualities for improvisation.

Improvisation training can take different forms. A simple example is to use simple magic tricks as a starting point for improvisational activities through which participants can be given a basic trick and to create a spontaneous performance, incorporating suggestions and inputs from audience. This encourages communication, interaction and feedback and enhances the performer’s ability to think on their feet through creativity, collaboration and adaptability (Lamont & Wiseman, 2005). Another simple example is to use magic as a tool for problem-solving. By giving the participants a seemingly impossible problem relating to design a magic trick and asking the group to brainstorm solutions, in order to develop their critical thinking and adaptability skills. Such activities are adopted to encourage learning through experimentation and learn from failure (Nisbett & Ross, 1980).

Overall, Magic, with creativity, adaptability, and unexpected, facilitates the development of improvisation skills. Skills and experiences learned from magic training can help individuals become more adaptable, creative, and confident in their ability to address uncertainty and transform challenges into opportunities for growth and innovation of organizations.

References

Akgun Ali E. and Lynn Gary S. (2002), New Product Development Team Improvisation and Speed-to-market: An Extended Model, European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 5, No. 3 2002, pp.117-129

Barrett F. & Peplowski K. (1998), Minimal Structures within A Song: An Analysis of “All of Me”, Organization Science, 9(5): 558-559

David Pogue (1998), Magic for Dummies, IDG Books Worldwide Inc., USA

Ed Rose (1998), Presenting and Training with Magic – 50 Simple Tricks You Can Use to Energize any Audience, McGraw-Hill Inc., USA

Fairley Stephen G. & Stout Chris E. (2004), Getting Started in Personal and Executive Coaching, John Wiley & Sons, USA

Gardner Howard (2003), Multiple Intelligences After Twenty Years, Harvard Business School of Education, USA

Hepworth Dean H., Rooney Ronald H. & Larsen Jo Ann (1997), Direct Social Work Practice – Theory and Skills 5th Edition, Brooks Cole Publishing Company, USA

Hugard J. & Braue H. (1974), The Magician’s Handbook, Dover Publications, USA

Lamont P. & Wiseman R. (2005), Magic in Theory: An Introduction to the Theoretical and Psychological Elements of Conjuring, University of Hertfordshire Press

Law Bridget M. (2005), Gesture Gives Learning A Hand, Monitor on Psychology, Vol.36 No.10 Nov 2005, American Psychological Association, USA

Nisbett R. E., & Ross L. (1980), Human Inference: Strategies and Shortcomings of Social Judgment, Prentice-Hall

Wan, S.C. (2006), An Exploration of The Use of MAGIC as a Training Method for Personal Development in Hong Kong, Dissertation submitted on the Completion of International Programmes in Educational Studies – M.Ed. (Guidance and Counselling), University of Newcastle Upon Tyne, 2006

Weick Karl E. (1998), Improvisation as a Mindset for Organizational Analysis, Organizational Science, Vol. 9, No.5, 9/10 1998, pp. 543-555

2025年1月12日成報的傑出義工會義人世界專欄《愛心魔法學苑 關愛及生命教育頻道報道》:

2025年1月12日成報的傑出義工會義人世界專欄分享了香港愛心魔法團1222義路同行感恩日:慈善團體 香港愛心魔法團 成立至今15年完成超過1000項社會服務,一眾義工朋友在義工路上一直不離不棄, 並肩而行帶出愛與關懷, 充分表現出跨世代和跨界別的共融精神, 這正是感恩遇見 – 「人人行義,坐言起行」!

【Hea住過新年】蛇年嘉年華 – 愛心魔法學苑持續發展頻道報道

慈善團體香港愛心魔法團的其中一家「愛心魔法夥伴」– HEA在去年支持了「香港愛心魔法團的1222義路同行感恩日」,在感恩日的分享當中,HEA的代表Hailey分享了他們一直以來都很支持社會服務和推動本土經濟發展。按照她說,HEA的成立是希望在香港和全球經濟環境面對各種挑戰的同時,他們能夠在銅鑼灣的鬧市中用較普及的價格提供一個輕鬆和悠閑的地方給大衆(尤其是上班族和年輕人)愉快地跟朋友和家人歡度生活,HEA本身有貓貓Café、小食亭、創意市集及各類型游戲,面積超過二萬尺。爲迎接蛇年,HEA更會主辦【Hea住過新年】蛇年嘉年華,讓大家有一個美好的農曆新年!有志在蛇年感受一下創業夢或大展拳脚的朋友也可以申請成爲檔主!

嘉年華日期:2025年1月17-19日,1月22-28日,1月29 – 2月4日

時間:每天中午12時至晚上10時

地點:銅鑼灣波斯富街114號寶榮大廈1-2樓 @HEA (在利舞臺對面、位元堂旁邊)

https://youtu.be/3vI2NXAAsp8

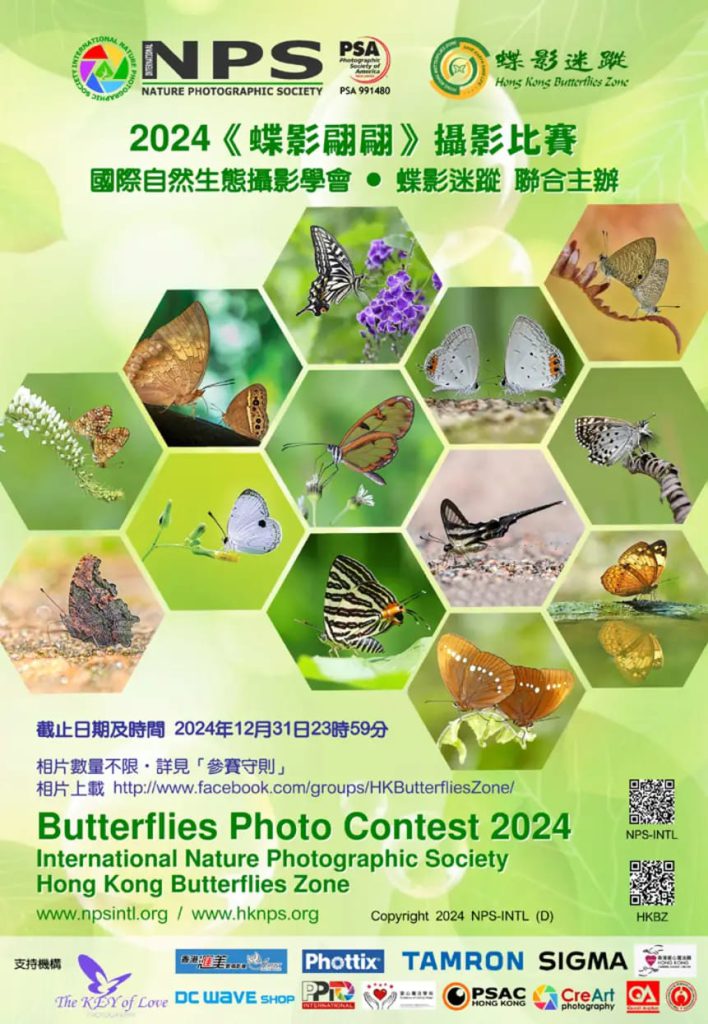

2024《蝶影翩翩》攝影比賽

帶出文化藝術的另一個景色, 捕捉自然之美 —— 《蝶影翩翩》攝影比賽即將拉開帷幕!

攝影愛好者們,準備好您的眼睛和相機,2024年度最令人期待的攝影盛事——《蝶影翩翩》攝影比賽,即將在這個春天綻放光彩!

比賽由NPS-Nature Photographic Society和蝶影迷蹤 聯合主辦,香港愛心魔法團以及我們愛心魔法學苑也是支持機構之一份子,大家也多多支持,見證大自然美麗的一面!